Economies are the lifeblood of societies, functioning as intricate systems that produce, distribute, and consume goods and services to tackle the universal challenge of scarcity. At its core, an economy involves networks of markets where buyers and sellers interact to allocate limited resources, shaping everything from daily life to global stability. Understanding how this works can empower you to make informed decisions and navigate financial landscapes with confidence. This article breaks down key concepts and flows in a way that is both inspiring and practical, offering insights to help you thrive in any economic environment.

By grasping the mechanics behind economic systems, you can better appreciate the forces that drive growth, manage risks, and foster prosperity. It is not just about numbers and charts; it is about human behavior, innovation, and the interconnectedness that binds us all. Let us delve into the fundamentals, starting with the basics that underpin every economic activity.

At the heart of any economy lies the principle of scarcity, which necessitates choices about resource use. Markets emerge as platforms for exchange, governed by supply and demand dynamics that influence prices and production. This interplay creates a foundation where microeconomics focuses on individual decisions, while macroeconomics looks at broader trends like employment and inflation. By exploring these elements, we uncover the rhythm that orchestrates economic life.

Understanding the Basics

To begin, consider the building blocks of any economy. These components work together to create a dynamic flow of activity.

- Transactions: Simple exchanges of money for goods or services, repeated endlessly and driven by human nature.

- Circular flow of income: A model showing interdependent loops between households and firms.

- Markets: Networks where resources are allocated through buying and selling.

- Scarcity: The fundamental problem that economies aim to solve by maximizing efficiency.

These elements form the groundwork for more complex systems. For example, the circular flow ensures that total income equals output value, creating a balance that sustains economic health. By understanding this, you can see how your own spending contributes to broader cycles of production and distribution.

Types of Economies

Different societies organize their economies in various ways, each with unique features and implications. The table below summarizes the primary types, helping you identify patterns in real-world scenarios.

Beyond these, economies can be classified by sector, such as agrarian, extractive, or emerging. Agrarian economies focus on minimal commercial flows with subsistence dominance. Extractive economies generate revenue from resource exports, often with little domestic reinvestment. Emerging economies feature large manufacturing and service sectors that drive wages and investment, leading to higher living standards. Recognizing these types helps you adapt to different economic environments and anticipate trends.

Key Economic Concepts

To navigate economies effectively, it is essential to grasp concepts like supply and demand, money, and economic indicators. These tools provide insights into market behavior and policy impacts.

The law of demand states that as price decreases, quantity demanded increases. Conversely, the law of supply indicates that as price rises, quantity supplied increases. Equilibrium occurs where supply meets demand, balancing production and consumption. Influences on these forces include consumer preferences, technological advances, and natural disasters, which can shift market dynamics unpredictably.

- Functions of money: It serves as a medium of exchange, unit of account, and store of value.

- Economic indicators: Key metrics like GDP, inflation, and employment reflect macroeconomic health.

- Credit creation: Central banks control money supply to manage stability, with credit expanding economic activity.

For instance, GDP measures total production value and links to employment and growth. Inflation and deflation arise from imbalances between spending and output, affecting purchasing power. By monitoring these indicators, you can make better financial decisions, such as timing investments or adjusting budgets.

The Circular Flow Model

The circular flow of income is a vital concept that illustrates how economies function as interconnected systems. It models the continuous exchange between households and firms, ensuring resources circulate efficiently.

- Real flows: Goods and services move from firms to households, while factors of production like labor and capital flow from households to firms.

- Monetary flows: Household spending becomes firm income, and firm payments like wages and profits become household income.

- Assumptions: Typically, households spend all income, and firms use all income for factors, creating a self-reinforcing loop.

Visual diagrams often depict sectors with arrows for payments, savings, trade, and inputs. In agrarian economies, flows are minimal and dashed. Extractive economies show export revenues leading to imports or investments abroad. This model highlights interdependent loops that sustain economic activity, reminding us of our roles in maintaining this balance through consumption and production.

Economic Cycles and Dynamics

Economies are not static; they experience cycles of expansion and contraction driven by factors like credit and human behavior. Understanding these cycles can help you prepare for fluctuations and seize opportunities.

The short-term debt cycle involves phases of credit-fueled growth and tightening. It begins with credit availability sparking expansion, where spending and incomes rise. If spending exceeds production, inflation may occur. Eventually, credit tightens, leading to recession or deflation. Central banks then lower rates to stimulate borrowing and spending, restarting the cycle.

- Credit availability drives expansion, with spending and incomes increasing.

- Inflation emerges if spending outpaces production.

- Credit tightens, causing recession or deflation.

- Central banks intervene to lower rates and encourage borrowing.

In the long-term debt cycle, debt buildup can lead to deleveraging, involving defaults, restructurings, wealth redistribution, or money printing. Forces driving these dynamics include transactions as the core unit, credit creation, and human nature influencing borrowing and lending. By recognizing these patterns, you can adopt strategies like saving during booms or investing during downturns.

Sectors and Real-World Examples

Economies are composed of various sectors, each contributing to overall flows and growth. From agrarian to emerging sectors, understanding their roles provides context for global economic trends.

- Households provide labor and capital to sectors.

- Sectors return wages and profits to households.

- External factors like exports and imports inject or leak resources.

- Government actions, such as taxes and subsidies, influence circulation.

For example, Australia's wool exports to China represent an injection into the economy, while China's coat imports act as a leakage. In extractive economies, such as petroleum exporters, profits often flow abroad without fostering domestic loops, leading to unsustainable growth. These examples show how global trade interactions can delink consumption from production, emphasizing the need for balanced economic policies.

Interdependencies in the Economy

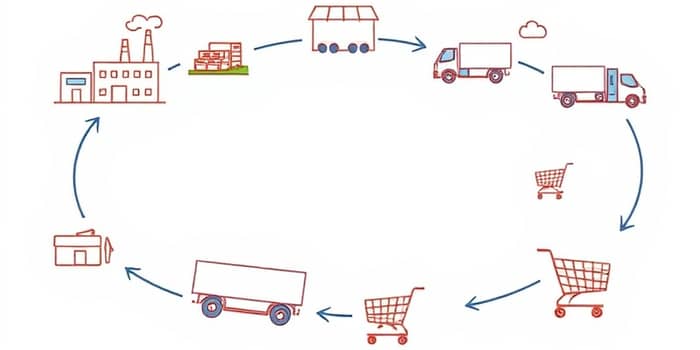

The production, distribution, and consumption cycle demonstrates how economic activities are deeply intertwined. Changes in one area ripple through others, affecting stability and growth.

Production involves creating goods and services using factors like labor and resources, often clustering for economies of scale. Distribution relies on transportation and markets to move goods, with high density lowering costs. Consumption drives demand, as household spending fuels production income. This interdependence means that shifts in consumer behavior can impact entire supply chains.

- Production clusters near labor or resources for efficiency.

- Distribution networks enable agglomeration, such as logistics hubs.

- Consumption patterns evolve with technology and social changes.

Forces like the Industrial Revolution have transformed these scales from local to global. Risks include leakages from imports or savings that reduce circulation, or diseconomies from congestion. By appreciating these connections, you can support sustainable practices, such as buying locally to reinforce domestic economic loops.

Conclusion

Economies are complex yet mechanical systems that thrive on balance and adaptability. From the foundational transactions to the intricate circular flows, each component plays a role in shaping our world. By understanding key concepts like supply and demand, money functions, and economic cycles, you gain practical tools to navigate financial challenges and inspire positive change.

Embrace this knowledge as a pathway to empowerment, whether in personal finance or broader societal engagement. Remember, economies are not just about numbers; they are about people, choices, and the collective effort to address scarcity. As you apply these insights, you contribute to a more resilient and prosperous future for all.

References

- https://www.futurelearn.com/info/blog/how-does-the-economy-work

- https://necsi.edu/the-dynamics-of-financial-flows-and-their-significance-for-development

- https://www.osl.com/hk-en/academy/article/how-does-the-economy-work

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Circular_flow_of_income

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PHe0bXAIuk0

- https://transportgeography.org/contents/chapter2/transport-and-location/economies-production-distribution-consumption/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mN5HPJYJzus

- https://block1economics.weebly.com/production-distribution--consumption.html

- https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCZ4AMrDcNrfy3X6nsU8-rPg

- https://www.cliffsnotes.com/study-notes/20878991

- https://www.citeco.fr/en/circular-flow

- https://sk.sagepub.com/ency/edvol/consumerculture/chpt/cycles-production-consumption

- https://fl-pla.org/independent/elementary/socialscience/section4/4c2.htm